Andrew Wyeth spent his summers in Cushing, Maine and his winters in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. His iconic masterpiece, Christina’s World, was painted in Cushing. The subject was Christina Olson, a Cushing neighbor who lived near Wyeth. He was inspired to paint her when he saw her crawling past his window. A degenerative disease left her unable to walk.

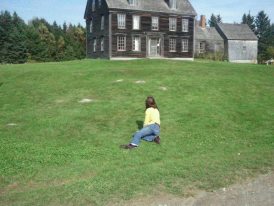

Featured prominently in the background is the Olson House, an 18th Century ship captain’s house which was in great disrepair by 1948. Its weather-beaten exterior provides the painting with its gothic feel and serves as Christina’s final destination.

Last fall we did the Farnsworth double-bill. We toured the Olson house then drove north for a Wyeth exhibition at the Rockland museum. In 2011, the Olson House was designated a National Historic Landmark. It has been open to the public for several years now. We started with the house then viewed the paintings at the Farnsworth. It seemed best to first connect with the space then view Wyeth’s interpretation at the Farnsworth.

Now, as the Washington Post reports, Wyeth fans in the mid-Atlantic have a similar chance to connect with the artist. Wyeth’s Chadds Ford studio is now open to the public. And just like in Maine, the studio tour is associated with an art museum. From the Brandywine River Museum, you can catch a shuttle to and from the studio, then you can view a permanent collection of Wyeth’s paintings on display at the Brandywine.